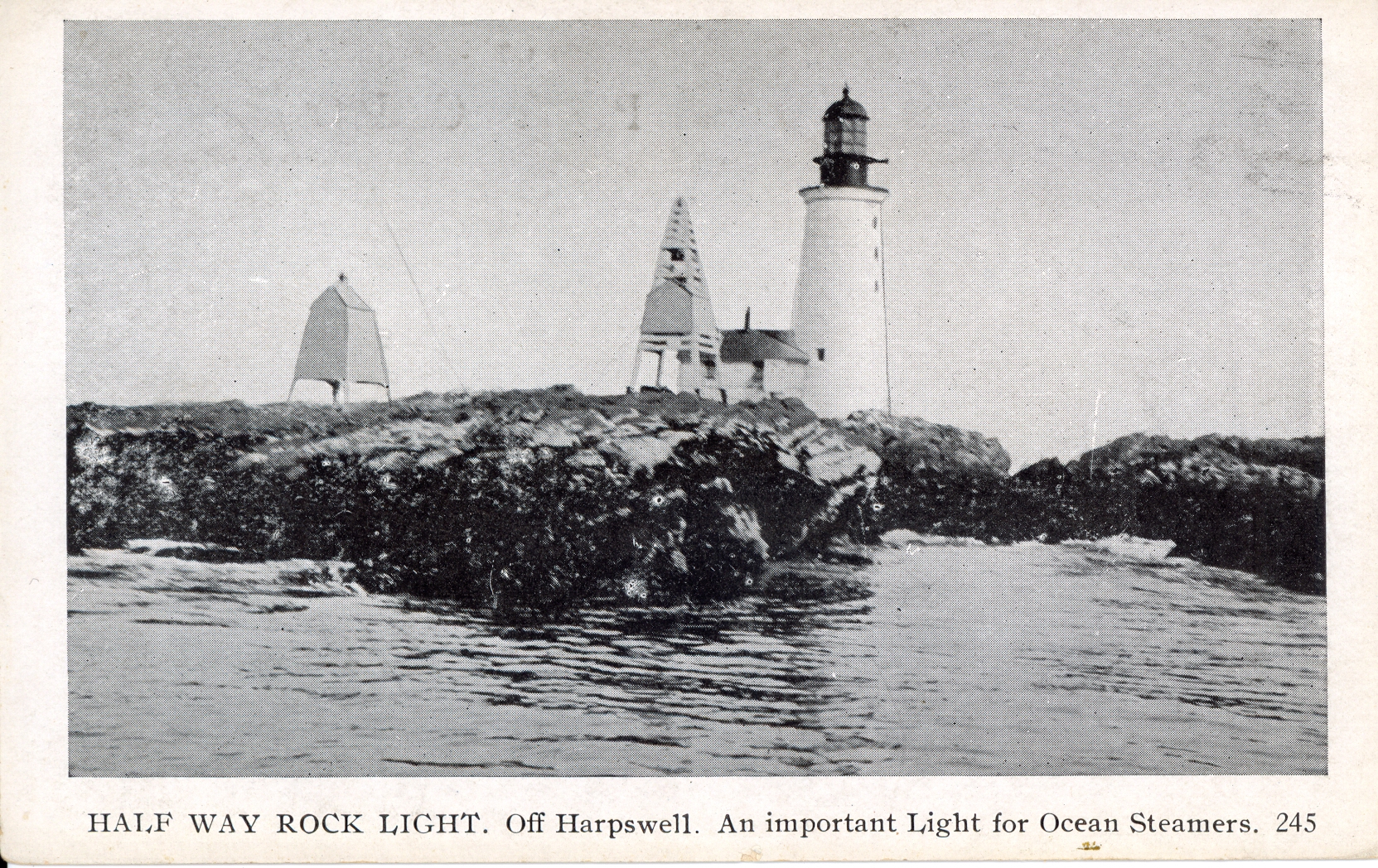

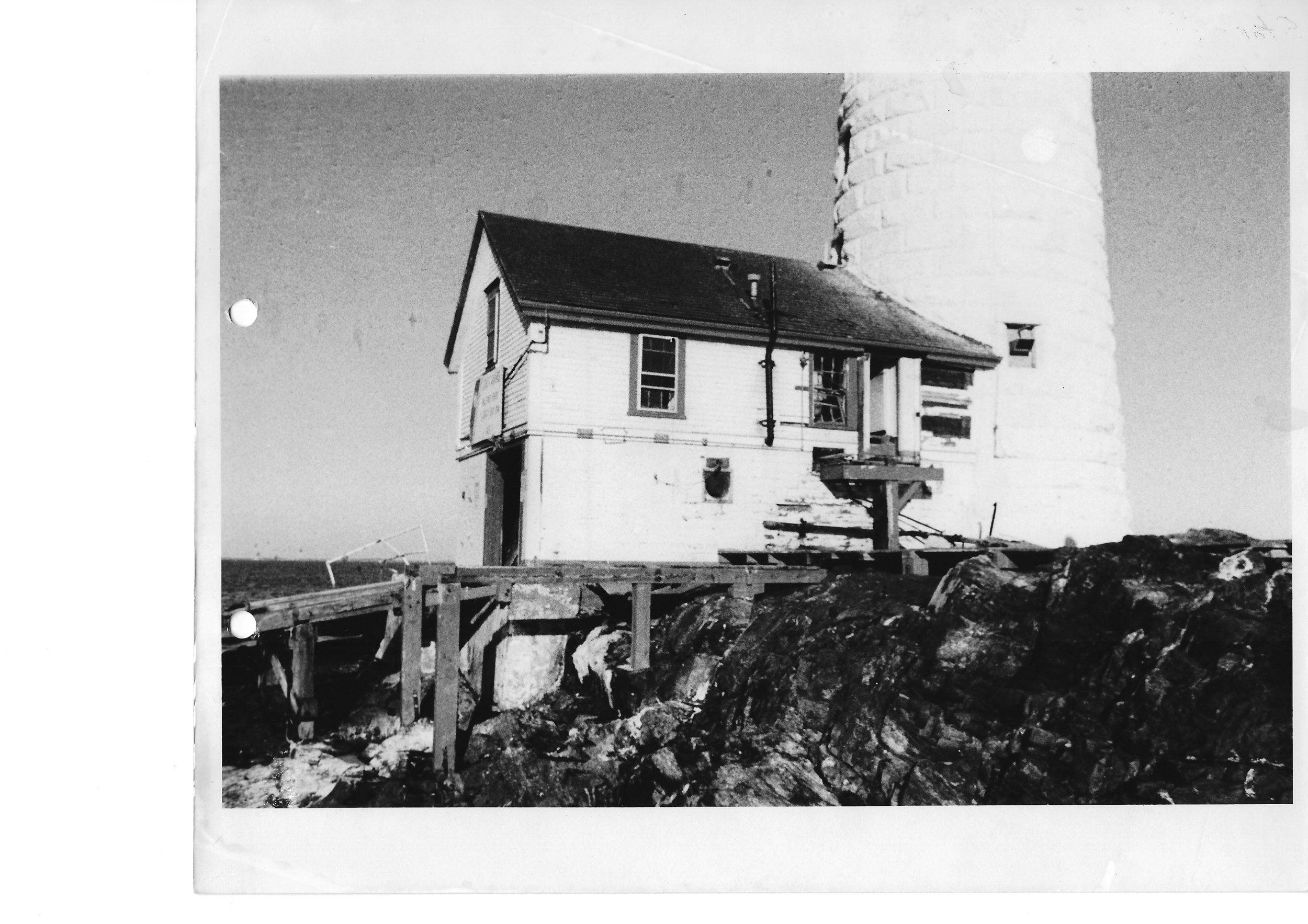

Halfway Rock Light Station was constructed in 1871 to serve as a beacon at the entrance to Casco Bay. Located ten miles from the mainland, it deterred shipwrecks from transatlantic vessels from Downeast, where the chain of lights were: “First Monhegan, then Sequin, Halfway Rock and then you’re in it.” It was deemed a ‘wave-swept’ or ‘stag’ lighthouse--one of just a few lighthouses in the U.S. deemed too dangerous for keepers to bring their families therefore operating in an unusual degree of isolation. The site consists of a seven-story granite tower and a contiguous two-story wood structure used as boathouse and solitary living quarters. The lighthouse was manned continuously from the time of its construction until 1975, when the beacon was automated. By 1980, the wooden boathouse and living quarters was slated for demolition--but concerned preservationists intervened. In 1988, the light station was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

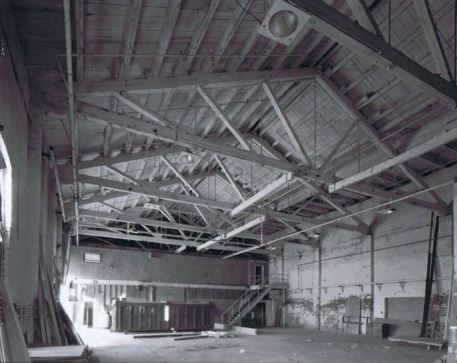

In 2014, Halfway Rock Light Station was deemed surplus property by the federal government and offered at public auction. Visitors agreed that the structure was in dangerously degraded condition; steel elements of the tower had corroded, all windows and doors were broken or missing, and much of the boat ramp had been destroyed. While the US Lighthouse Protection Act required that surplus lighthouses be offered to qualified non-profit custodians for free, every organization that expressed interest in Halfway Rock withdrew in response to its condition.

The Presumpscot Foundation, however, was unaware of the chance to acquire Halfway Rock Light for free, and participated in the public auction that followed. Of the three interested parties involved in the majority of the bidding, TPF was the only one interested in preserving the site for its history, and it won the auction. Still, difficulties did not end there: a bureaucratic error in the 19th century meant that the lighthouse itself was federally owned but the rock still belonged to the State of Maine! The ensuing legal process lasted over a year, delaying preservation efforts.

And there were still more challenges: restoration efforts at Halfway Rock Light were not eligible for federal tax credits (because there was no feasible income-producing use), but the deed secured from the federal government required that all work be compliant with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards. Add to that, of course, a location plagued by transport and weather difficulties that destroyed three small boats and two outboard motors in the first year of work. Despite all these obstacles, the Presumpscot Foundation moved forward, securing 200 historic images, 75 news stories and 26,400 pages of logbooks.

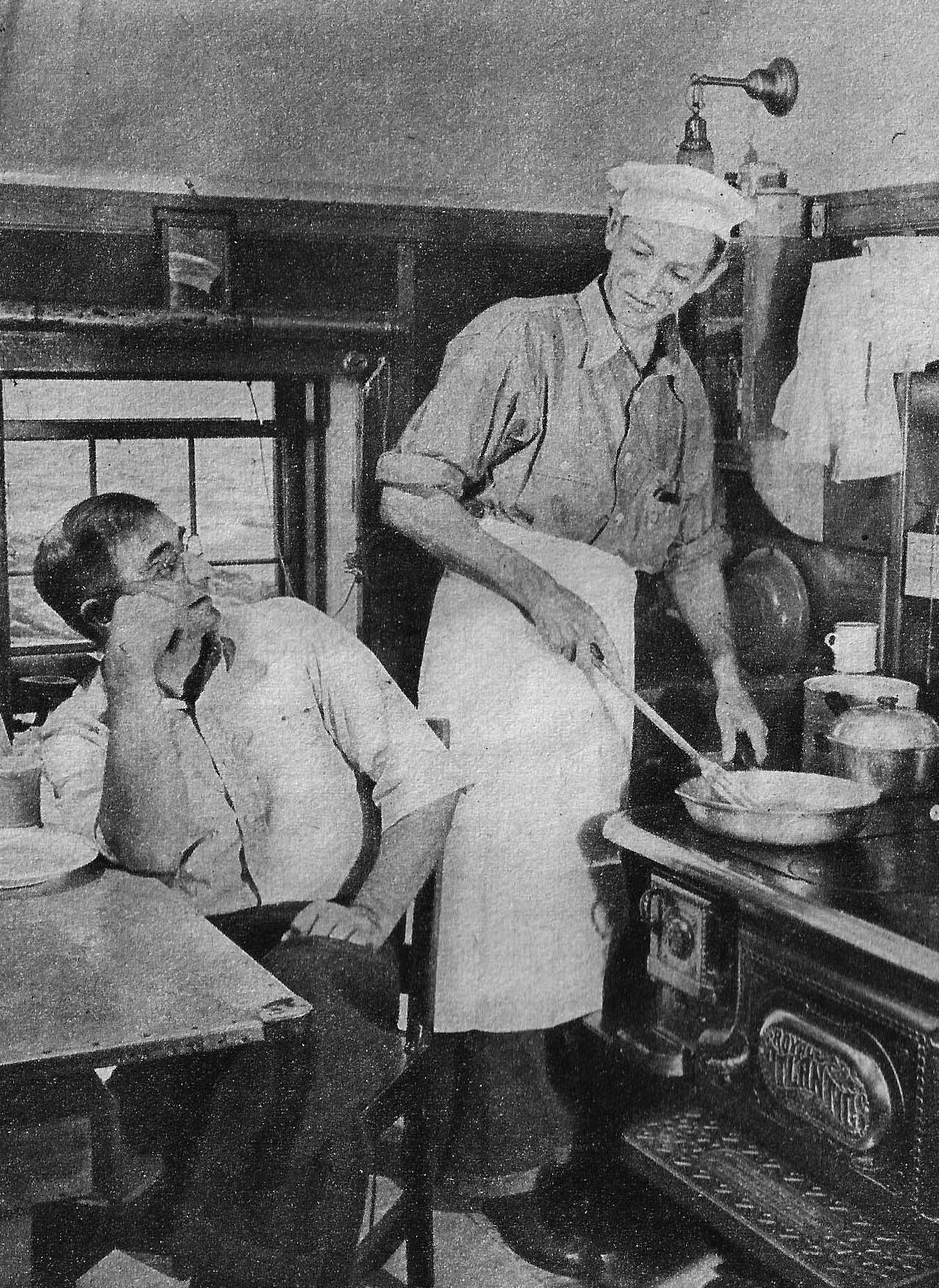

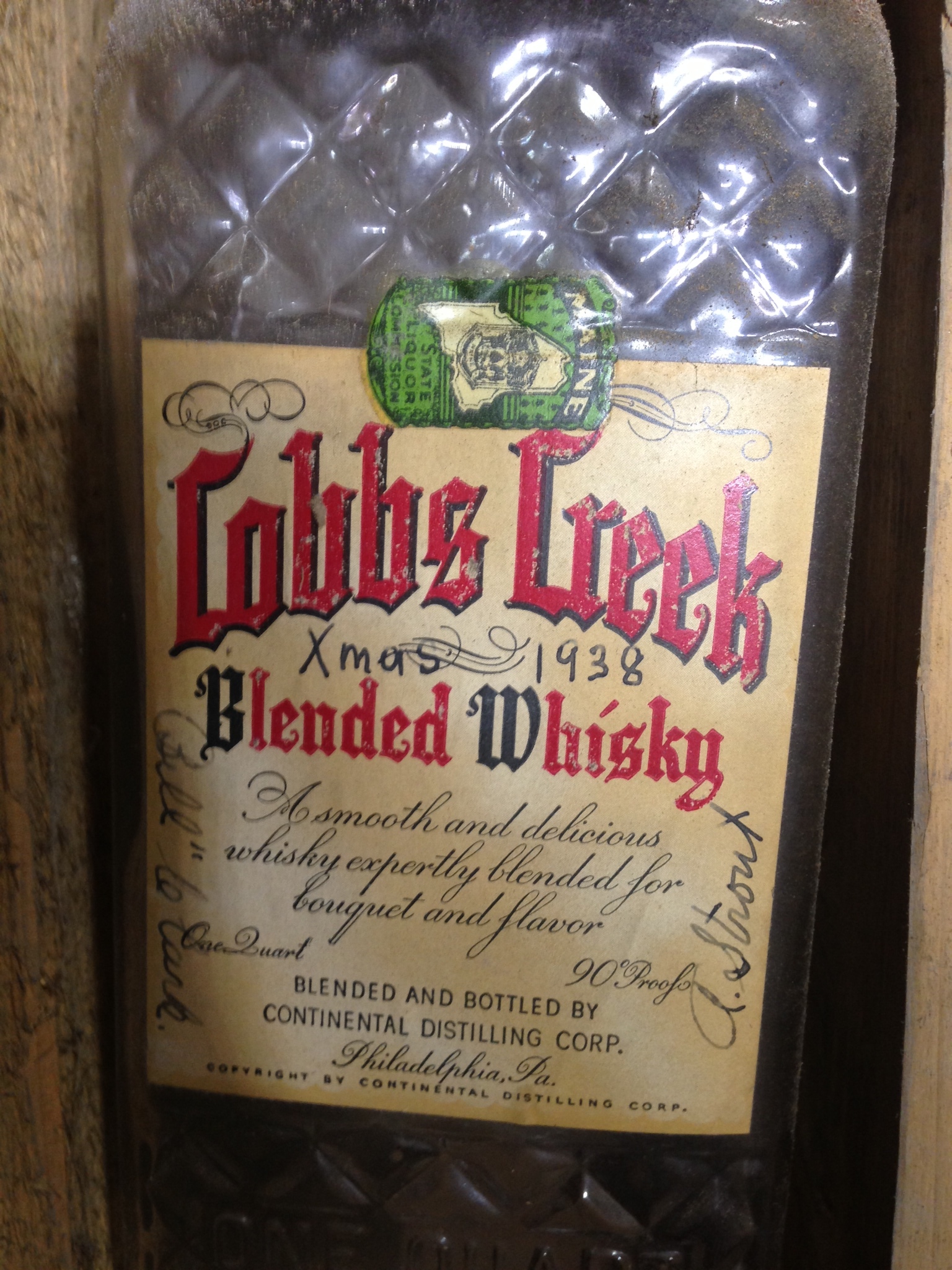

Work to restore the buildings to a 1950 period of significance is now complete; the 80-foot boat ramp was reconstructed and a small boat and guest mooring have been placed at the site; the exterior of the two-story boathouse and living quarters was repaired and replaced; and the masonry repointed and the iron ring atop the seven-story tower realigned. On the interior, the second-story living space and kitchen were restored, a modern electrical system and composting toilet installed; and original Douglas fir bead board paneling (once concealed under five layers of wall coverings) has been revealed. Removal of the remnants of a 1939 doorway that had been destroyed during later reconfigurations revealed a liquor bottle placed there on Christmas Eve, 1938 by keeper Arthur Strout and assistant Bill Clarke, likely marking their disgust about the disbanding of the U.S. Lighthouse Service scheduled for 1939. And a small boat and guest mooring have been placed at the site.

While public access will always be restricted because of the site’s inherent dangers, general interpretation of the lighthouse and its history are readily available through a new website. Thanks to the unflagging efforts of the Presumpscot Foundation, Halfway Rock Light Station—a site of great significance to Maine’s maritime history, endures. It is quite literally a shining example of the preservation of Casco Bay’s extraordinary heritage.