The Story

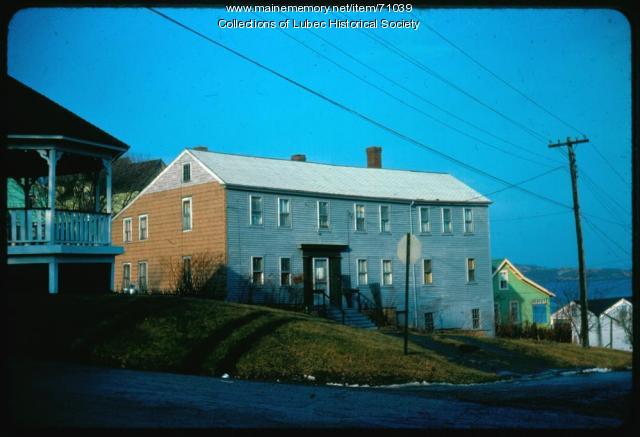

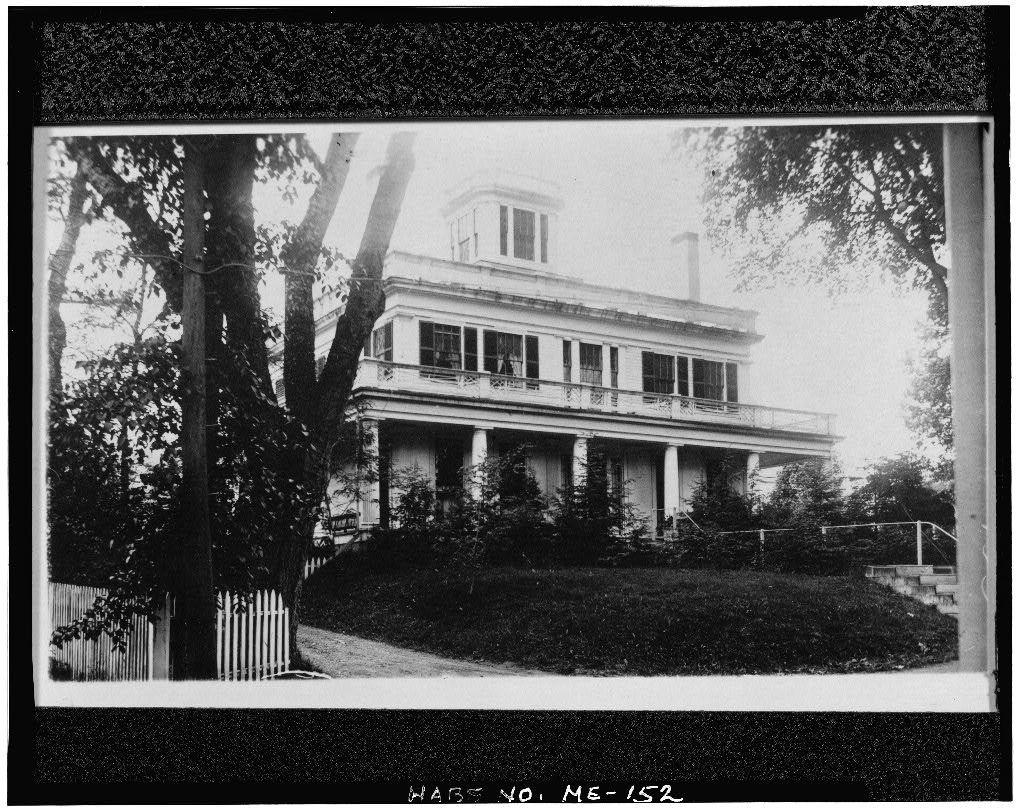

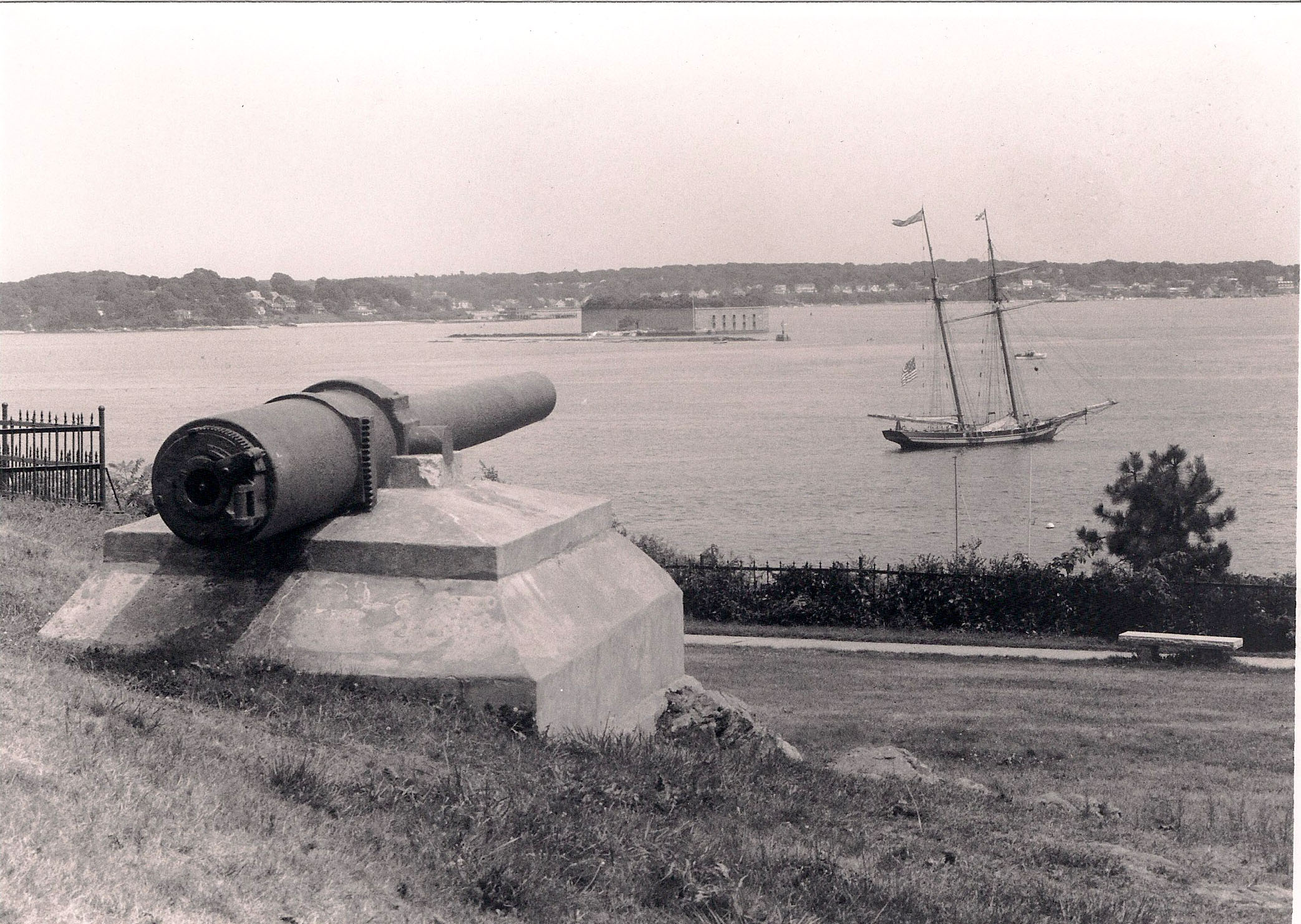

The bucolic ideal of a Maine camp or cottage is inextricably linked to the history of the Pine Tree State. In defined areas along the coast, such as at Mount Desert Island and Prouts Neck, large-scale and sometimes year-round cottages were built by summer residents --“rusticators”-- who arrived by ferry and train to escape cities to the south. More typical along the coast were modest, small-scale cottages. Inland, an array of rustic camps permitted Mainers and visitors to get back to nature and enjoy the healthful benefits of fresh air, the outdoors, and simple pursuits such as fishing, boating and hunting.

The Threat

Current design trends have led to the wholesale removal of historic features in old camps and cottages, stripping them of their character and authentic qualities. Other classic getaways are being demolished and replaced with gargantuan structures that loom over neighboring homes and change the scale, views, and historic access points of rural communities.

The Solution

As one camp steward says, “We don’t consider ourselves to be the owners of our camp. Instead, we consider ourselves to be its newest stewards. The owners and their descendants cared for the camp and its story for more than 100 years, and we are privileged to have the honor of doing so for the years to come.”

Maine Preservation believes that the following efforts will lead to improved outcomes for our state’s historic camps and cottages:

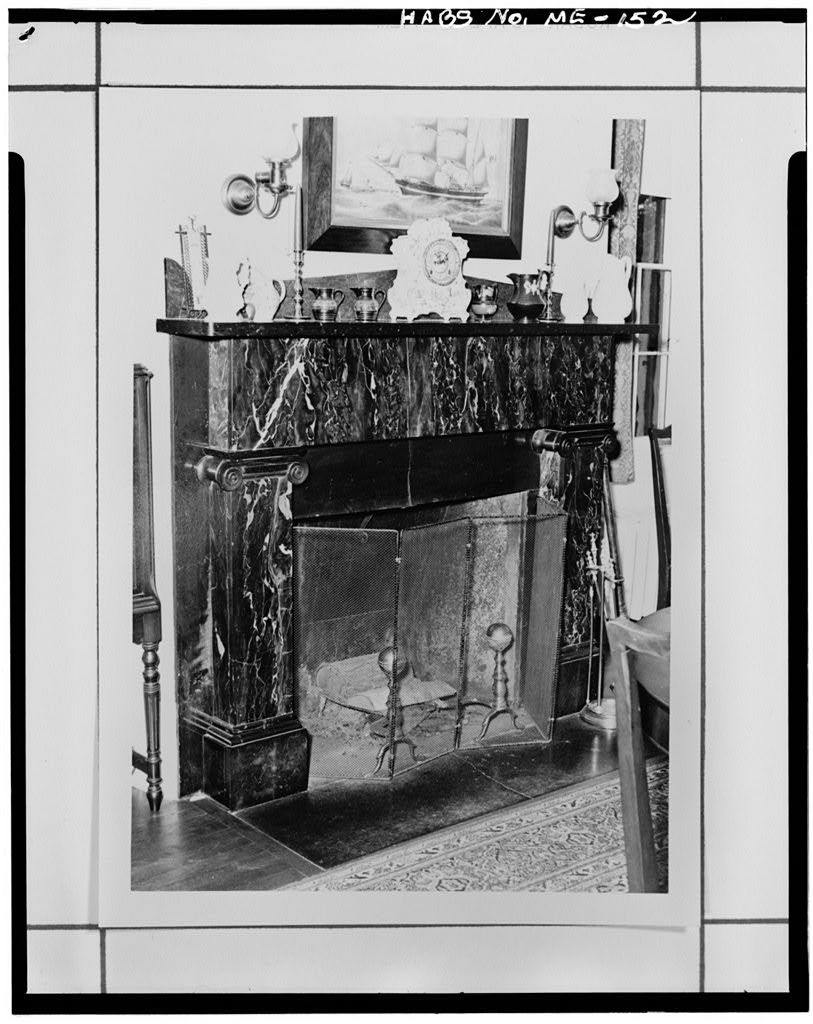

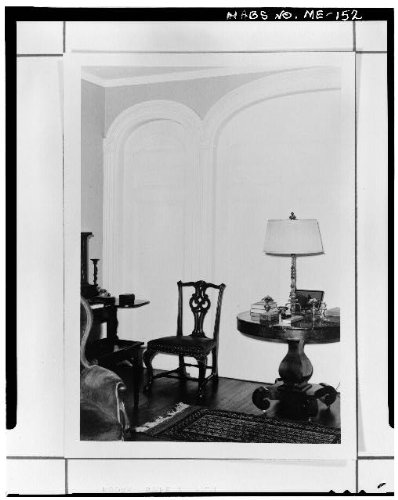

• Educating owners about ways to modernize and update cottages and camps without destroying the durable historic materials that give them their character

• Celebrating the authentic sense of place and history that characterize Maine’s vacation places and their role as an escape from the hyper-connected world in which we live

• Instilling preservation principles and locally protecting historic camps and cottages

• Limiting the scale of new houses based on their surroundings