The Story

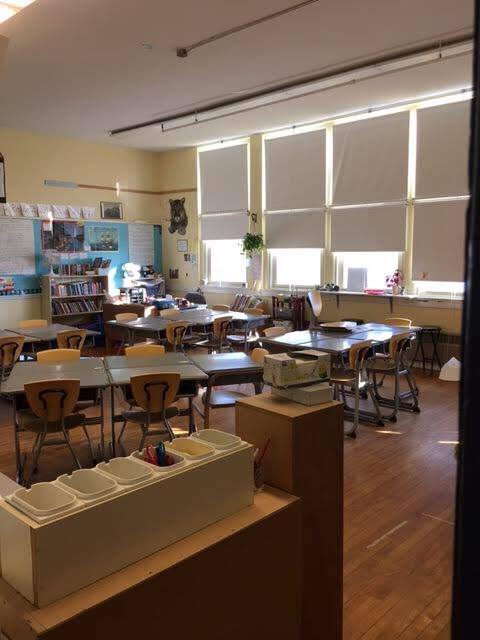

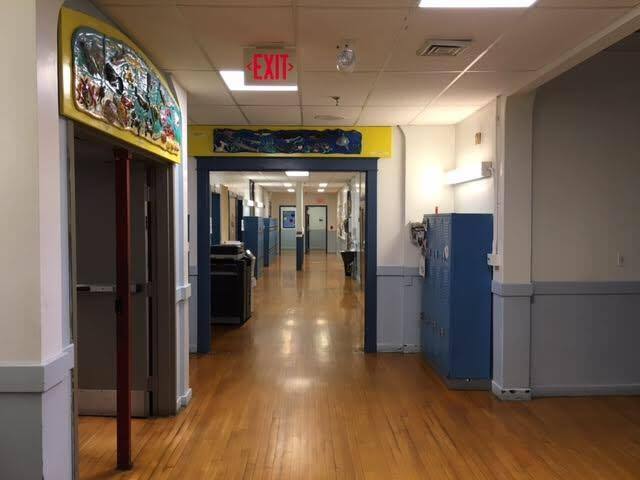

The 28,200 square foot middle school on Knowlton Street was designed in 1925 by the well-respected Augusta architecture firm of Bunker and Savage and falls under the jurisdiction of the Camden-Rockport School Administrative District 28. It was renamed after Mary E. Taylor in 1957, who served as the school’s principal from 1916-1953. Many local residents attended school in this original Mary E. Taylor (MET) building, which holds significant importance with the community. The building is in relatively good condition with only minor repairs needed. The major needs for the building include ADA access improvements and updates to codes. Since 1957, the MET building has continually expanded and now contains 122,000 square feet. The original building has been nominated for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Threat

In 2015, Camden and Rockport voted down a $28 million bond to both construct a new middle school and spend $3 million to rehabilitate the MET building. In June 2017 voters again went to the polls, but the bond had been lowered to $25.2 million and included specific language regarding the demolition of the existing historic school. Public concern about the demolition was eased by assurances from Maria Libby, Superintendent, that despite what the bond stated, rehabilitation of the MET building was still on the table. This time, the bond passed.

The current design plans for the new school do not include rehabilitation of the MET building; in its place plans call for an activity field. While the school board has stated they are willing to consider viable reuse proposals for the building, they have stipulated that if a private developer rehabilitates the building, they are interested in half of the existing space being used for their offices. Additionally, legal counsel has advised the School Administrative District that they cannot commit to a lease longer than 4 years as a tenant, and 10 years if they act as a landlord. The conditions they have set are such that private development will be extremely cost-prohibitive.

A preliminary rehabilitation estimate for the building is $3.4 million for the stand-alone use as the School Administrative District offices. The SAD has been talking about the need for new administrative office space for more than a decade, but the school board has now voiced concern regarding the types of people who may be visiting the offices and whether or not this would be a security issue on an active school campus. While controlling access to school property is of paramount importance, throughout Maine there are scores of existing private housing units and other buildings that abut schools and practice fields. The configuration of the MET building on the campus allows for reuse of the building with minimal disruption to the school.

The Solution

The Mary E. Taylor School is in good physical condition and demolition costs are expected to run more than $200,000. In addition, the social, environmental and economic opportunity costs of reusing rubble from the building for on-site fill contradict the goal of working together to ensure this historic landmark remains both a functional tribute to quality education, and the encouragement of community sustainability and lasting civic values. This well-built building has had an excellent history of low maintenance costs. Demolition provides a disservice to the concept of re-use and does not set a positive example concerning the SADs vision to ensure sure students are, “working cooperatively and collaboratively.”

In Maine, 14 historic schools have been adapted into housing units since 2008 utilizing the state and federal historic rehabilitation tax credits. In addition, there are dozens of school reuse examples from other states, including:

- Sonora, CA: historic school building is now the school administrative offices, local arts council and a local radio station

- Knoxville, TN: senior housing

- Woodstock, GA: satellite technical college campus and technology hub for business startups and students in the former gymnasium

- Thomasville, GA: center for the arts

- Kansas City, MO: multi-use recreation center; assisted living center; adult day care center; Boys & Girls Club

The School Board should heed the calls of the community to pro-actively evaluate the reuse potential of the building, including a broad range of adaptive use solutions. Innumerable communities have buildings and houses that border on school campuses, and the majority have not erected barriers to community members visiting sports practices or other extra-curricular activities. While located on the edge of an active campus, there are numerous options for reuse for the Mary E. Taylor School that will not interfere with or pose safety issues to school campus users. The community has too much to lose historically, socially and economically if this well-built neighborhood anchor is allowed to be demolished.