In Searsport, the c. 1905 cast-iron fountain, designed and patented by Henry F. Jenks of Pawtucket, RI, was cut off from its power source in 2005 and had fallen into disrepair. With support from the Town and Searsport United Methodist Church, the newly formed Searsport Historic Preservation Commission restored the fountain to serve as a point of pride in the community’s history. The fountain had been moved from its original location down the road where it had been installed to provide water for horses tied up in town. Working with the Searsport Select Board and Town Manager, the Commission media blasted and refinished the fountain, secured a new electrical connection to the Methodist Church, and got the water flowing once again. The project was financed in part by a successful calendar fundraiser. While horses no longer stop in for a drink, the beautifully restored fountain is once again a piece of public art for all to enjoy.

Burnt Coat Harbor Light, Swan's Island

The Town of Swan’s Island and the Friends of the Swan’s Island Lighthouse completed their joint restoration of the Burnt Coat Harbor Light on the island’s Hockamock Head. The navigation aid had been automated and the station abandoned, until the town acquired the property in 1994. The subsequent 15-year, $900,000 restoration revived the light tower and keeper’s house from 1872, oil house from 1895, and bell house from 1911, carefully matching historic materials and dimensions: quarter-sawn wood siding, lime-based cements, and precision-turned catwalk stanchions. The site is open for public tours, with the keeper’s house apartment available as a short-term vacation rental. In the process, the project brought together the local and summer communities on the island to honor local history and maritime traditions, and created a common focal point for the twenty-first century. This achievement will be celebrated along with the sesquicentennial of the lighthouse in August of this year!

New Purinton Brothers Block, Augusta

The 1916 Neo-classical commercial block was originally occupied by the Purinton Brothers Company, which provided its customers with heating coal and oil. It later served as office and retail space, with a number of restaurants running through its basement space, but it had been altered over the years and underused. Owner’s Matthew and Heather Pouliot recognized that the building anchored the southern end of Augusta’s Water Street Historic District and agreed with their peers that it needed to be brought back to life. The Pouliot’s reclaimed the interior of the residential second floor by removing drop ceilings to reveal a 20-foot octagonal monitor roof, unleashing natural light into the shared corridor. The redevelopment exemplifies the power of state and federal historic rehabilitation tax credits, especially considering the building is already fully leased, adding nine new residential units and three first floor commercial spaces.

Riverdam Mill Complex, Biddeford

Using state and federal historic rehabilitation tax credits, Port Property rehabilitated Buildings 3 & 4 of the former Saco Water Power Company facility into a vibrant, mixed-use community in Biddeford. The 90,000 sq. ft. development includes 71 residential units anchored by Blaze Brewing Company and Stone Fort Distillery on the ground floors. The project team had to remove existing underground mill raceways and remedy compromised masonry walls to bring these brick, steel, and concrete buildings back to life. The damaged portion of Building 3 was transformed into a riverfront patio, while reactivation of the complex provided a critical connection to complete the city’s pedestrian Riverwalk. Port Property sought to foster a community-based space for living, and in keeping with their inclusive community goals, incorporated 10% of its units as affordable housing.

Norma and Greg Rossel, Troy

It takes courage and determination to save a meaningful place. Thankfully for the residents of Troy, Norma and Greg Rossel have both, plus an innate appreciation for old buildings. When it was discovered that the future of the town’s only true meeting space, the Troy Union Church, was in jeopardy, the couple stepped up. They started with a donation jar at the local general store.

The Troy Meeting House Society constructed the building in 1840 as a Union Church. The group of Troy residents raised funds and sold pews to create a non-denominational space that could be used by all. The white, rectilinear building features a mix of architectural details, a prominent box belfry with four spiralets on the front portion of the roof, and a relatively unadorned interior. The overall form, closed cornice pediment, wide frieze, corner pilasters and projecting window hoods all point to the Greek Revival style, while inset lancet arch and tracery motifs on the pilasters, trim, and doors exude hallmarks of the Gothic Revival style. General maintenance kept the building in working order for more than 150 years, but serious issues like a leaning steeple were left unresolved for several decades. Reality set in in the early 2000s and it was either fix it or lose it.

The easiest path for the small membership would have been to let gravity and mother nature run their course. The Rossels had a different plan. They weren’t going to give up on the landmark down the road from their home. Looking back on the project, Greg proclaimed that “buildings say a lot about common aspiration, ambition, and pride. 175 years ago, citizens together fashioned a classical landmark that was grander than any of their individual homes, barns, or shops and placed it on a high spot on a main road so all could see it. It said – we are a town.” They may not have known it, but the Rossels were working to preserve something larger than a building, they were sustaining community through a common cause. They forged the path and won supporters along the way.

Norma served as the Restoration Project Coordinator, while Greg assumed the role as chair of the restoration campaign. Having been a member of the Troy Union Church for over 40 years, Norma was no stranger to the structure’s storied past. With help from Christi Mitchel at Maine Historic Preservation Commission, they researched and successfully nominated the church to the National Register of Historical Places (2011). Their responsibilities were all encompassing – project management, fundraising, and communications. Norma took advantage of her newly acquired grant writing skills from participating in Maine’s Encore Leadership Corps (ENcorps) and managed willing volunteers. Greg, a boatbuilder by trade, developed the scope of work, coordinated contractors, and documented every detail of the project from start to finish. He remarked that when you take something apart, you probably should have an idea of how to put it back together!

Using visual evidence from historic postcards, the group was able to restore the church to its original appearance. The work spanned several phases and amounted to precision surgery on the church. Lead contractor, Preservation Timber Framing, first had to remove the entire tower to access and remove the damaged king truss, central to the roof structure of the church. They then lowered in a new truss system that was constructed adjacent to the church that improved upon the original design. Lowering the tower back atop the church marked a great victory for the project’s supporters.

Local carpenters worked alongside Preservation Timber Framing to learn about the basics of timber frame construction. Project volunteers also had to remove the 20th century drop ceiling that had put stress on the failing structure. Students from nearby Mount View High School and Unity College volunteered removing layers of wallpaper to uncover the original plaster. Locals contributed to the effort, with the use of locally-sawn timber, copper work atop the steeple, hand carved wood trim for the tower, window restoration, and preservation of the original plaster.

The momentum and outreach generated at the local level attracted support from across the state. The Maine Steeples Fund supported an initial assessment of the building and two subsequent phases of restoration, totaling over $60,000. Further grant support came from the Maine Community Foundation, Morton-Kelly Charitable Trust, and the Leonard C. & Mildred F. Ferguson Foundation. Altogether, the Rossels and company secured over $100,000 in grants. More importantly, those grants were matched by $190,000 in individual gifts, an impressive fete for a preservation project of any size! [Volunteer labor was estimated at an additional $30,000.]

By the time Troy Union Church was restored, hundreds from the community and church had contributed to the effort, but it would not have been possible without the fortitude and leadership of Norma and Greg. A restored Troy Union Church fills a central need as the only space for community meetings, performances, and events in Troy, echoing the reason for its inception in 1840 – once again putting Troy back on the map.

Burnt Island Light Station, Boothbay Harbor

On March 3, 1821, the 16th Congress appropriated $10,500 for the construction of the Burnt Island Lighthouse, along with two others along the coast of Maine. Secretary of Treasury William H. Crawford was assigned the task of selecting a suitable site, eventually selecting Burnt Island at the entrance of Boothbay Harbor. On May 25th, the federal government purchased the island for $150 from local businessmen Jacob Auld and Joseph McCobb. The government’s builders constructed a stone lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling using granite blocks cut from the island. On November 9, 1821, Keeper Joshua B. Cushing lit up the Burnt Island Lighthouse for the very first time. Thirty other keepers followed in his footsteps to illuminate Boothbay Harbor’s guiding light.

Built just one year before Maine became a state, the Burnt Island Light Station has served mariners for over 200 years. In fact, it’s considered the state’s oldest unaltered lighthouse. For most of that time, a light keeper served as on-site steward, but following automation in 1988, the attention and resources needed to conduct routine maintenance on the lighthouse, keeper’s dwelling, and outbuildings were lost.

Ten years later, the Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR), with its Education Director, Elaine Jones spearheading the effort, gained possession of Burnt Island through the Maine Lights Program. A biologist by training, Elaine wanted to transform the island environment into a living classroom for science educators and students from across the state. The fact the island had a lighthouse of course was not lost on her. With the help of volunteers, they cleared fallen trees and brush, established public paths and gardens, added benches, built public restrooms, and installed a docking system and moorings to improve access. The culmination of these efforts was marked by the construction of an Education Center in 2006, complete with sleeping accommodations, to host day and overnight educational programs.

In 2008, Elaine partnered with the newly formed non-profit, the Keepers of Burnt Island Station (KBIL) to work towards the common goal of restoring the island’s gem. Their “Keep the Light Burning” capital campaign solicited donations from hundreds of people through gift-giving and special events, acquiring the funds needed to restore the station through private sources rather than taxpayer dollars.

Prior to commencing work, Elaine dedicated a great deal of time and effort conducting extensive research to document, justify, and guide the restoration process. She compared her newfound love of history to a puzzle, always needing to look for the next piece. Standards and procedures for restoration were developed in cooperation with the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, United States Coast Guard, and Maine Bureau of General Services. She obtained architectural drawings and photographs from the National Archives and Coast Guard Historian in Washington D.C., and the Coast Guard’s Civil Engineering Unit in Providence, RI. This research also led to the creation of a living history program in 2003 that is now facilitated by the Keepers of Burnt Island Station. The program centers on the powerful story of Joseph Muise, one of fourteen former keepers and keepers’ families who Elaine interviewed as part of an oral history project. It tells of Joseph’ life as a keeper and the way him and his family got by day to day.

The moment of truth finally arrived in 2020, when Elaine oversaw the half a million-dollar restoration of the light station, including exterior repairs, new roofs, heating system, septic system, interior upgrades, and the installation of a waterline from the mainland. The masonry light was still structurally sound, but in desperate need of repointing to reverse years of deterioration and prevent future water infiltration. The extensive metal elements, including the roof, decking, railing, astragal, and ventilator ball were severely rusted, requiring careful restoration. The lantern was restored, and windows reintroduced to recreate the lighthouse’s 1950s appearance, while making some concessions to permit its continued use as a navigational aid. Improvements to air circulation were also made to prevent the build-up of mold, mildew, and moss. The work shed, boathouse, and coal bunker all received new roofs, while the restoration of the keeper's dwelling (1857) included the installation of new historically appropriate windows to replace those that had been added in the late 20th century.

J.B. Leslie Co. of South Berwick and Marden Builders Inc. of Boothbay Harbor, Maine, served as the primary contractors, the former handling masonry and metalwork and the latter, carpentry. The project started in mid-June and lasted through October 2020. On top of the unique challenges of a historic restoration project, crews also had to carefully navigate the logistics of mobilizing large equipment and supplies to the island.

Burnt Island Light Station celebrated its Bicentennial in 2021 as a beautifully restored historic site for the people of Maine. It is now a place of learning for students, teachers, and members of the public; and will continue to be a recreational site for boaters and a navigational aid for mariners. Burnt Island and its rich history is now perfectly positioned to serve the public for another 200 years.

St. Ann's Churchyard, Gardiner

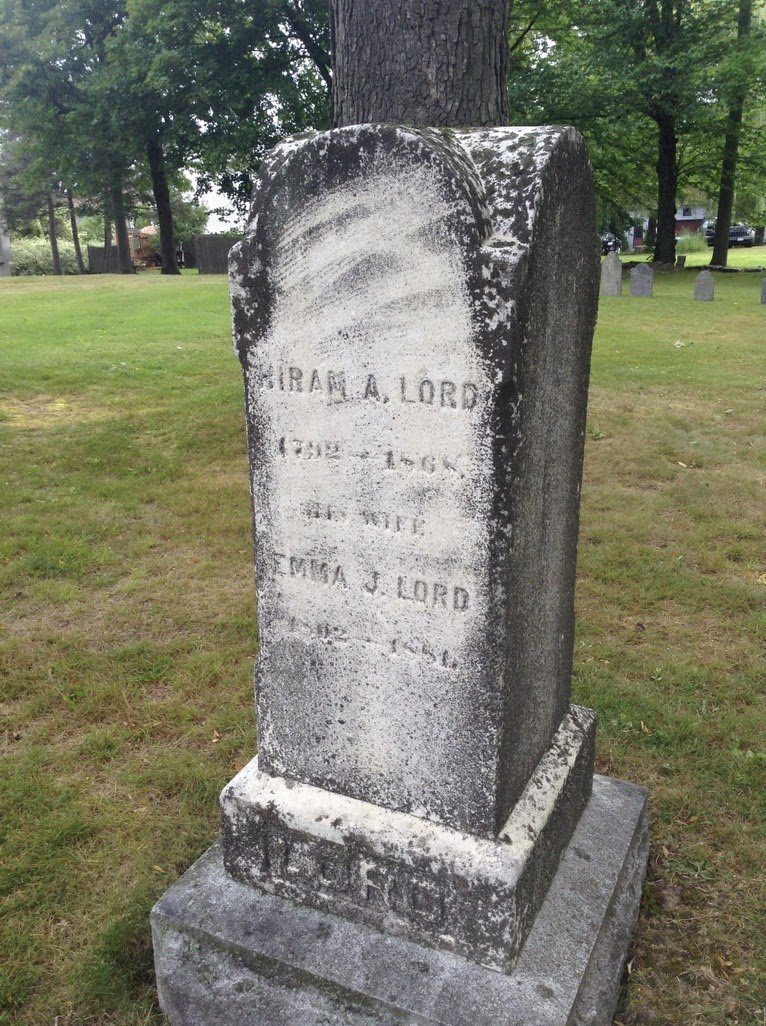

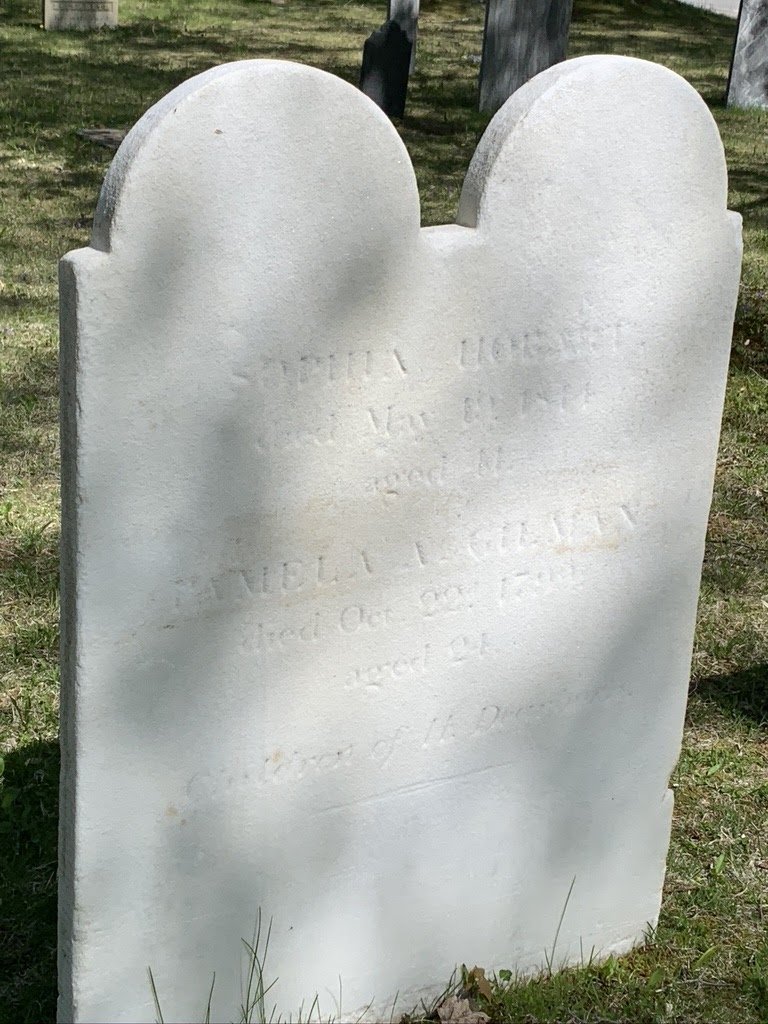

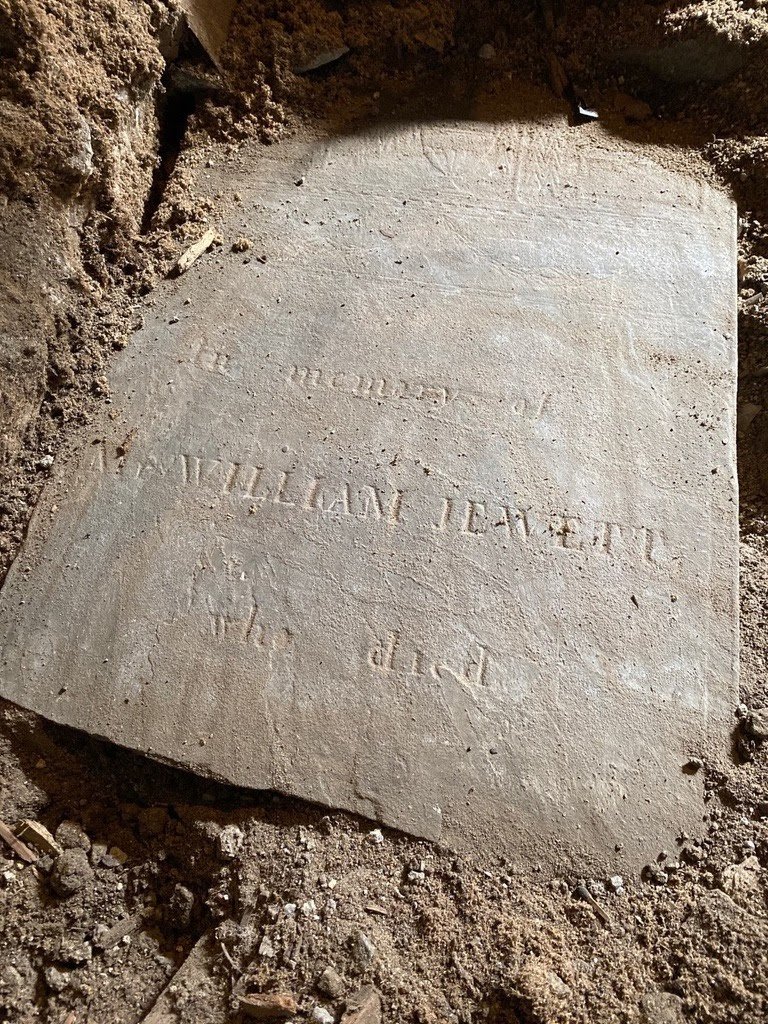

In 1771, Dr. Silvester Gardiner established St. Ann’s Church, which included the region’s only meeting house and churchyard where early settlers were buried. The churchyard includes the graves of Revolutionary War veterans and families tied to the area’s pioneering businesses, including the 1791 gravestone of Dorcas Gardiner and Dr. Gardiner’s son, William, who died in 1787. By 1823, the churchyard was so full that burials were restricted. The 1840s opened space as families moved graves south to the more fashionable Oak Grove Cemetery.

Unfortunately, the diminishing interest in the churchyard did not bode well for the existing burials. Town records indicate that 65 gravestones stood in 1911, a time when the churchyard was no longer used and had fallen into disrepair. Fundraising efforts in 1889 and 1924 to improve the churchyard fell short and did little to inspire action. By 2014, only eleven burial stones remained. Another unsuccessful effort gathered and recorded 30 fallen and broken stones and graded the yard to locate others. Another 21 gravestones and many footstones were relegated to the church basement, generally forgotten, undocumented, broken and hidden.

Enter William “Bill” King, Jr., who first encountered the churchyard in 1987 while locating the graves of his Gardiner family ancestors, first cousins of Kennebec Proprietor, Dr. Silvester Gardiner. When he returned to the churchyard fifteen years later, Bill found the remaining stones upended, broken and flat. Bill shared the concerns of Christ Church parishioner and historian, Jody Clark, who recruited fellow-parishioner and groundskeeper, Hank McIntyre, and Gardiner Public Library’s Special Collections Librarian, Dawn Thistle, to restore the churchyard. Together, this determined team worked for seven years conducting needed research and completing physical restoration work.

Volunteers initiated re-placement of stones, working from archival research, intact stones, and two photographs pre-dating stone-toppling. Placement was confirmed by discovering matching material underground, and broken stones were repaired and cleaned. The team credits the project’s success to the literal heavy lifting by friends, family, and parishioners of Christ Church, which owns the churchyard and enthusiastically supported the project. The restoration of the physical grave markers was guided in part by Cheryl Patten of the Maine Old Cemetery Association (MOCA).

The local group also hired New Hampshire firm, Topographix, to conduct Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), which aided in grave identification. They identified fifty anomalies, outnumbering remaining stones. The group also discovered the stones in the church basement – one was even found supporting the church’s foundation. When missing, new bases were cast or cut from stone material. Volunteers epoxied stone breaks, filled cracks, repaired chips, and even re-carved inscriptions. Some 50 gravestones and 17 footstones were cleaned and placed, returning them to historic locations, restoring the historic burial ground.

The successful efforts to restore St. Ann’s Churchyard is both a cause for celebration and a call for action to reflect upon the importance of preserving the hallowed grounds that dot Maine’s landscape. As Bill King explains, “they are a very important repository of our history, holding the last remains and documentation of our founders and builders of our Maine culture and communities.” Along with completion of the project, the team also celebrated another occasion, reconsecration of the churchyard.

Mt. Merici Convent, Waterville

When a significant building can no longer serve its intended purpose, one of the greatest challenges is finding a new use that both respects its past and satisfies a need in the community. An empty convent at the Mt. Merici Academy, a place central to the educational, residential, and spiritual legacy of the Ursuline Sisters presented this very challenge.

Six Sisters came from Quebec to Waterville in 1888 at the request of Reverend Narcisse Charland, pastor of the St. Francis de Sales church. Their mission was to educate the children of the French-Canadian mill workers who were moving to the city after the construction of the Lockwood Mills. The first school was built in 1888 and a convent of the order was built in 1891, on a lot adjoining the St. Francis de Salle church in downtown Waterville. The Sisters purchased a 100-acre property outside the downtown in 1911 to establish a larger convent and boarding school for girls. In 1957, a new school building was built on the site and in 1967 a new convent followed. The old and new buildings of Mt. Merici Academy served as a Catholic school for girls from 1912 until 1967, when it became a coeducational day school. The convents served as the principal residence for the Ursuline Sisters stationed in the Diocese of Portland from 1912 to 2005. By then, construction was completed on the nearby Ursuline Care Center, to serve as a retirement home for the few remaining Sisters.

Relocation left the convent vacant, mothballed, and without a use for over fifteen years. Because of its original design, the building was primarily comprised of very small sleeping rooms along the long corridors of the convent. This left potential reuses difficult to identify. There was also the question of how the architecturally significant chapel would be utilized. Patience and faith in finding the right fit paid off.

Looking to address the housing shortage in the community, the Waterville Housing Authority turned to the empty convent. The building once intended to house the Ursuline Sisters could be put back into service to provide much needed affordable housing for Waterville’s senior citizens. The reuse proposal echoed the ethos of its original owners the Ursuline Sisters, whose motto, established by founder St. Angela Merici, is Serviam or “I will serve”. The project received critical support from local leaders, including former Mayor Nelson Megna and now former Mayor Nicholas Isgro, and officially proceeded with approval by the Housing Authority’s Board of Directors.

The reuse project successfully paired State and Federal Rehabilitation Tax Credits with Low Income Housing Tax Credits, which require the building also be brought up to MaineHousing energy efficiency standards. Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credits were available with the nomination of the larger Mt. Merici Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places. The district includes the convent, school, and cemetery. Critical financing was made possible by Camden National Bank and Federal Home Loan Bank of Boston.

Modern improvements to the convent included new windows and new finishes in the apartment units and hallways. The project team, led by Portland-based Archetype Architects and Herbert Construction, combined the existing Sisters' sleeping cells to create 28 independent apartment units. The addition of an elevator and restrooms permitted public use of the original chapel. Although the chapel was deconsecrated as part of the project, the vaulted wood ceiling and stained-glass windows still provide residents a place for quiet reflection. The space originally used as a cafeteria for the neighboring Mt. Merici Academy was converted into a community room and the Sisters’ library relocated for residents.

The Waterville Housing Authority and its partners re-envisioned a uniquely configured floor plan to provide 28 units of affordable housing, while preserving the architectural elements of the 1967 modernist convent. As buildings and sites from the 1960s and 1970s become eligible for historic designation and preservation incentives, we need to continue to rethink and reimagine what places are important and meaningful to Mainers. Certainly, the Ursuline Sisters’ tradition and culture of service, through both acts and the creation of spaces, is worthy.

Broad Bay Congregational Church, Waldoboro

Religious buildings are among the most historic and architecturally significant structures in our communities but are also often the most imperiled. Maintenance and repair of these large, intricate buildings can quickly become a financial burden to aging and shrinking congregations. And when the burden becomes too great to bear, repurposing these sacred spaces can be a challenge. Thankfully, after the congregation of one of Waldoboro’s oldest church buildings relocated to a newly constructed space, the then fledgling Broad Bay Congregational Church stepped in to take the reigns as its new steward.

Looking to further its mission in the community, the 30-member congregation purchased the former First Baptist Church in 2002. While Waldoboro’s First Baptist Church formed in 1834, the Greek Revival building was not erected until 1838. In 1856, the congregation raised the church and built a brick vestry underneath along with a small steeple. A much larger building campaign took place in 1889 with the addition of a large tower and steeple as well as integrating newly fashionable Italianate features such as rounded arch, stained glass windows. The tower served as a new narthex, while addition of circular pews and frescoes enhanced the interior.

What began as a condition assessment of their new historic building, quickly evolved into a long “to-do list” that they knew would stand in the way of opening their doors to the community. Among the pressing needs was the steeple’s failing timber frame structure and an unreliable foundation to hold it all in place. Access to the sanctuary was limited to interior stairs and a wooden ramp that stretched to the neighboring property, while bathrooms were isolated on one floor.

The Broad Bay Building Committee selected architecture firm Barba + Wheelock to guide the master plan for the transformative project with Chris O’Hara of Structural Integrity filling the role of structural engineer and Auburn-based H.E. Callahan Construction Co. serving as the construction manager. Preservation Timber Framing completed the necessary repairs to the steeple.

Curious onlookers watched as contractors had to cut the tower away from the building and carefully float it using huge steel beams, so that a new foundation could be poured. With the tower’s timber frame repaired and lowered onto solid footing, work commenced on reconfiguring the narthex. The construction team combined the existing flanking stairs in the narthex and installed a lift to provide enhanced access between the sanctuary and the fellowship hall on the ground floor. The re-configured entry space now engages the congregation and visitors with the historic sanctuary space by replacing the existing wall with a glass curtain system. Architect Nancy Barba remarked that “the new entryway serves as a light-filled community gathering space and meets an emotive need to pause, wait for friends, reflect on the historic building, and feel the peace of this quiet, but active place.”

The tower also received a much-needed new roof and bell cradle. A new heating system, additional insulation, and efficient lighting improved the energy efficiency of the 140-year-old structure. ADA-compliant bathrooms were built out on both floors and the front doors to access the narthex are now located at grade.

The Maine Steeples Fund supported the early coordination for the project and later granted $60,000 towards restoration work on the tower. Altogether, the vigorous capital campaign raised over $900,000 in just one year. The congregation received a huge boost, after successfully applying and receiving a $250,000 grant from the highly-competitive National Fund for Sacred Places.

When faced with the prospect of mounting repair needs and even the potential of outgrowing the space, the Broad Bay congregation chose to remain in place rather than build new so that they could remain in downtown Waldoboro. They chose to open their doors to the community and host a variety of social services that would otherwise not have a space. By adapting and enhancing accessibility between the sanctuary and the fellowship hall, the historic church is now better positioned to serve as an approachable and sustainable center of the community.

Scruton Block, Lewiston

It is not unusual for buildings to evolve. The inevitable change in ownership and use, technological advances, and shifting stylistic tastes result in structures acquiring new layers. This was the case with the former Marcotte Furniture Store in downtown Lewiston. The four-story building along the once bustling Lisbon Street corridor, was dominated by a full-length aluminum screen from the 1960s. While modern screens or slipcovers were a popular way to refresh a commercial building in the mid-20th century, they weren’t all executed well. And in the case of Marcotte Furniture, it added a foreboding wall to downtown Lewiston that hid vacant upper stories and distracted from an underutilized commercial space on the first floor.

Enter Jules Patry, owner of Lewiston staple, DaVinci’s Eatery. Knowing its true potential, Mr. Patry purchased the old furniture store in 2017. He looked for tools to redevelop the building when he came across the Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit program. To qualify, the slipcover would have to go. That was the easy part. The hard part – the building could qualify for the tax credit, but only as part of a larger historic district. Undeterred, Mr. Patry looked to his neighbors along Lisbon and Main Streets for cooperation to unlock the benefits of a historic district.

These efforts resulted in the official listing of the Lewiston Commercial Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places in October 2018. The designation recognized the historical and architectural significance of 82 buildings in downtown Lewiston. The Lewiston Water Power Company sandwiched the thoughtfully laid out commercial corridor between the mills along the Androscoggin River to the west and the residential neighborhoods to the east. Architectural styles in the district reflect the span of its development from 1850 to the mid-twentieth century, and included Greek Revival, Italianate, Romanesque Revival, Beaux Arts, and Art Deco. The City of Lewiston supported this effort and has since provided resources on its website to educate property owners, businesses, and developers about the financial incentives for investing in the historic downtown area.

What was first known as the Scruton Blcok, was built in 1873, and housed a bank on the first floor, before quickly transitioning into the retail space. In anticipation of creating the historic district, Mr. Patry worked to remove the metal screen and modern storefront to unveil the beautiful details of the Romanesque Revival commercial block. The sun once again shined down on the rounded arch windows, brick corbelling, and cast-iron ornamentation along the storefront.

Using historic photographs and architectural clues, the design team led by Noel Smith of Studio A Architecture, was able to recreate a historically appropriate storefront, prominently featuring a front entry with original fluted columns and a pressed metal ceiling. Upstairs, the new apartments offer modern amenities and features that take advantage of the tall window openings and high ceilings.

Work returned the historic character to the building's facade and in the first-floor retail space while creating three stories of new residential apartments. The City of Lewiston provided TIF dollars to complete sidewalk improvements, add additional egress towards the rear of the building, and enhance stormwater management on site. Scott Hanson of MacRostie Historic Advisors walked the project through the historic tax credit process.

The transformation of the Scruton Block was not only about reactivating an underutilized historic building, but also about catalyzing redevelopment efforts in downtown Lewiston. The project added 12 much-desired market rate apartments to the downtown along with a vibrant first floor commercial space teaming with natural light.