July 2020

Here’s your opportunity to be a homesteader in Maine in a fabulous Downeast location.

The National Park Service is soliciting proposals to take on the McGlashan-Nickerson House as a long term lease. You bring the repairs, and the property is yours to use essentially rent-free for 60 years. It’s a great opportunity to be a part of something very special.

About the opportunity

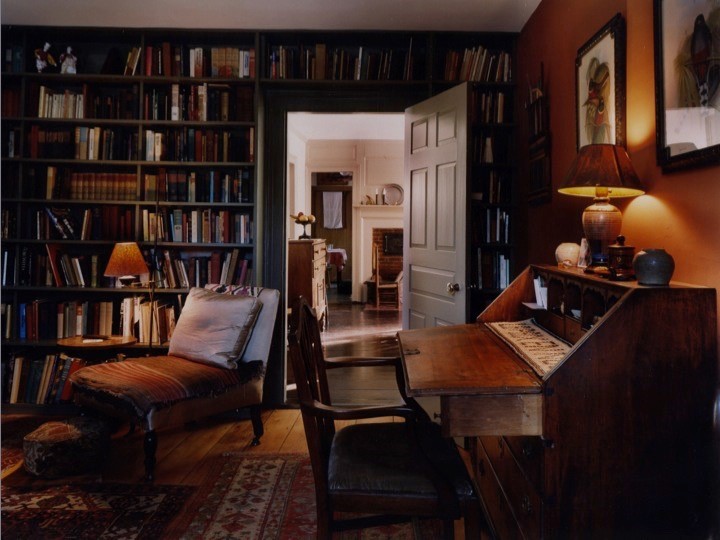

The house offers approximately 5,400 SF in the main house and 750 SF in the barn. It features three bedrooms on the second floor of the main block and a number of others in the ell. The first floor features a parlor and dining room with pantry off the central hall with Italianate style details including molding, panel doors and two tiled fire places. A hall extends to the kitchen through which is the woodshed. The ell extends to the carriage barn which features a large sliding door, a second story loading door, and three horse stalls. The basement is unfinished concrete floor with a cut red granite stone foundation.

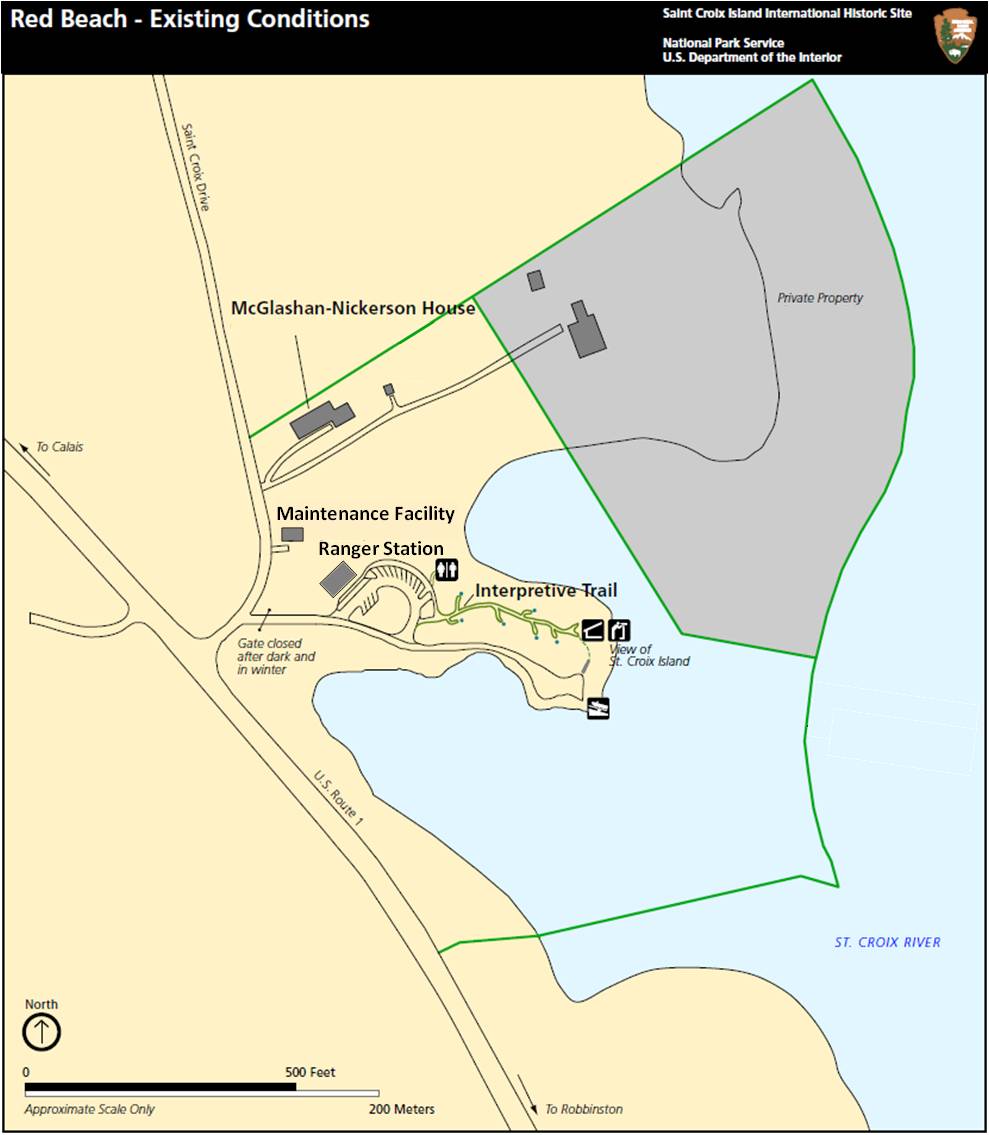

The boundary of the Lease Premises includes approximately 1.5 acres which is a portion of land historically associated with the property. The boundary includes the house, barn, shed, gravel access and parking area, and an entrance drive which is a shared access to the neighboring property; a Gothic Revival style cottage built in 1854 and is also listed on the National Register of historic Places.

The NPS acquired the property in 2000 to serve as a temporary visitor center, office, and housing until 2014. It has since been used for storage but mostly shuttered.

The house requires significant stabilization and rehabilitation work including roof replacement, lead paint, radon, and asbestos abatement, and repair or replacement of windows and siding. There is no heat or central air to the building. The furnace needs replacing and the fuel tank has been removed. There is electricity to the building but it is out of date. In addition, the well and septic system needs to be assessed prior to occupancy. The Lessee will be responsible for all stabilization and rehabilitation expenses to meet Secretary of Interior Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties.

Learn more about the opportunity here:

Request for Proposal Overview - scroll down for the RFP, images of the house, sample lease, and much more: https://www.nps.gov/articles/mcglashan-nickerson-house.htm

The full details on the opportunity and how to apply: https://www.nps.gov/sacr/getinvolved/dobusinesswithus.htm

Maine most Endangered Places Citation

The Story

During the nineteenth century Red Beach was a thriving Calais community built around the now-defunct Maine Red Granite Company and the Red Beach Plaster Company. A survivor of that heyday is the McGlashan-Nickerson House, constructed in 1883 by Scottish immigrant George G. McGlashan. Acquired shortly thereafter by Calais Justice Samuel H. Nickerson, the rambling two-story Italianate house sports a long ell extending to a carriage barn. The house sits on six acres and is among the largest and most architecturally significant houses in Red Beach and is the only one of Italianate style. It shares a long drive with and the 1854 Gothic Revival Joshua Pettegrove House, that has a landscape designed by a follower of Andrew Jackson Downing., the founder of American landscape architecture. These houses are both individually listed in the National Register of Historic Places and form the southern boundary of the village running upriver to the north. Just downriver, adjoining the McGlashan-Nickerson House property, sits the visitor’s center for the St. Croix International Historic Site, owned by the National Park Service but located well to the east on an island in the St. Croix River.

The Threat

In 2000 the National Park Service (NPS) acquired and rehabilitated the McGlashan-Nickerson property to house a variety of administrative functions. In 2013 NPS began exploring alternate uses for the property as, after building a new visitor’s center to the south, it no longer needed the house. Sadly, NPS had already stopped painting and repairing the historic residence abdicating its mission to maintain the property. Maine Preservation is surprised that in the just-released Draft Environmental Assessment, the National Park Service stated its preference to dispose of the house WITHOUT the underlying property, requiring any bidder to move the structure. If no bidder willing to initiate a move comes forward, which NPS acknowledges is likely, the Park Service will demolish the house.

The Solution

For two years Maine Preservation has offered and continues to offer to work with the National Park Service in partnership with the Maine Historic Preservation Commission to find a new owner for the McGlashan-Nickerson House who will stabilize and rehabilitate the house and agree to manage the house in a manner compatible with the adjoining visitor center. For the National Park Service, as the federal agency responsible for our national parks, monuments and all other properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places as well as for the protection of the historic integrity of these places, to demolish this National-Register listed historic house violates its own mission.